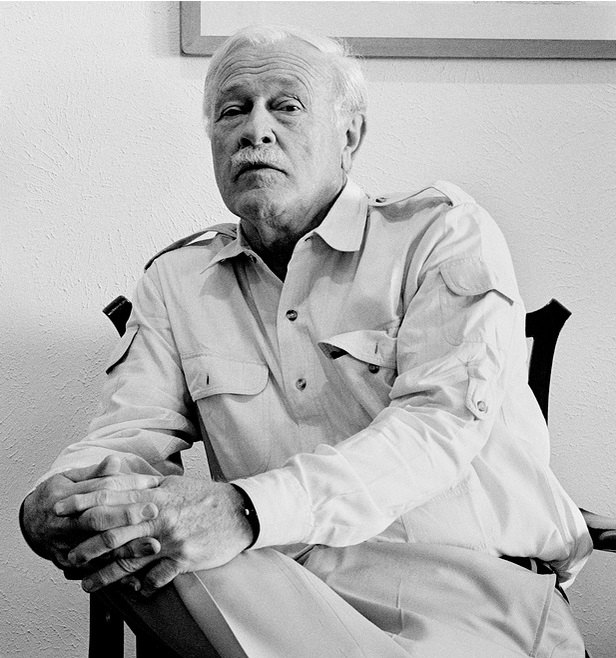

Franck Van Deren Coke – famous photographers

Van Deren Coke started his photography career quite early. He came to know Edward Watson and worked with him for a couple of months, after which Franck enrolled for a course in photography conducted by Ansel Adams.

Van Deren Coke graduated from Kentucky State University with two degrees – one in general history and the other in the history of arts. During WWII Frank served in the USA Navy. After the military period he worked in the family business (wholesale hardware trade) for 11 years.

In 1953 he studied history of art and sculpture at Indiana University.

In 1958 Van Derek Coke began to teach photography and history of arts at Florida University (Gainesville). He also worked for some time upon his unfinished thesis at Harvard, but switched becoming adjunct professor at Florida University. Coke’s true interests lay elsewhere and the thesis would have taken up too much attention. In 1961 he provisionally lectured at Arizona State University for two semesters.

In 1962 Coke was offered curator’s position at Arts Museum of the University of New Mexico (Albuquerque). The new job engulfed him even more than photography, at first. But soon, being appointed head of the department of arts at the same university, he discovered a passion for humanistic photography. After there was a period of directorship at George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film. Then Coke returned to New Mexico State University to occupy his previous position as curator of the college arts museum.

Franck Van Deren Coke was very engaged in teaching photography to the young and eagerly shared his visions of the process. One of his interviews allows us to see this process from within – through Franck’s own eyes, so to say. The course was open for all university students. As with many colleges, the plan was pyramidal in its structure. The base of the pyramid was made up of freshmen groups. While the course was hugely popular, Coke said that only a few students came with a firm desire to make photography their lives’ dedication. The majority signed up just because they had some interest in the subject – among other things – and decided that this particular course was better than the alternative photojournalism or the general knowledge of photography. As the result, the course was extremely crowded.

But already at the next level the numbers were halved. Those, who didn’t want to pursue a career in photography, usually left by then. The third level ‘silted’ away some more, leaving us three or even two groups (of the original 12). Then, according to Van Deren Coke, the teachers could be sure they had people resolute enough to make the art of photography their life’s choice.

And that was the time for advice.

One of the steps on the way, according to Van Deren Coke, was taking a yearly course in art history conducted by professor Newhall, and some studies in art criticism. When students attended those lectures they developed an understanding they had lacked before – understanding of the point and matter of photography. Coke said that was the core – and an oversight on the part of various alternative courses. The technical aspect was reviewed just casually. Everything you needed to master the shooting technic could be covered in less than three lectures, as Franck Van Deren Coke estimated. And then students themselves started coming for more or found knowledge on their own. Some students would even launch into realms outside Professor’s own reach and grasp. For that reason the college always started with asking why somebody wanted to specialize in photography and what expectation he or she had about it.

Students’ expectations are an interesting thing. It would be equally interesting to know what professors think about them. And what professors themselves want – how do the aspirations of both parties and their mutual expectations interact, so to say?

Van Deren Coke said the college didn’t pursue any particular goals with the students who had enrolled for the course. The young people were eager to know more about the world and themselves. They were not supposed to become assistant professors, then lectures. And the teaching was not a system for turning out masters of photography at the end. The college was realistic about it. It stood clear that the demand for photographers was not very high and that only very few would have the perseverance to become real masters of art in this sphere. On the other hand, without the degree there would hardly be a professional photographer’s job – hence the real benefit from education.

Coke said that in terms of practice the college program was weak. They hardly taught any skills to speak of. And it was always stressed at the very beginning that the course had little in common with applied photography.

Answering the question about his teaching methods at the third level, Van Deren Coke said that he was not much involved at that stage, but there was no strict program. They used to invite guest lectures who were experts in specific narrow aspects of photography and had the ability to relate their knowledge to other people. The college did not even make plans on a semester-by-seme

Franck Van Deren Coke’s own lectures didn’t follow a particular plan either. Living not far from college, he would invite students over to his place. They came on Tuesdays at ten and left around half past noon or at one p.m. The lectures took form of the round-table discussions concentrating on three things. The first was the critical approach to photography – past and present; after that they usually talked about the past, looking for common things and analogies, or brought up different historical issues. It was not like they went over the history decade by decade. The third thing they would take up was students’ own works. There were always some people – three of four – who specialized in history of photography.

When asked about, whether those history students took any pictures of their own, Coke said that yes, of course, they did. But those photos were discussed in a slightly different perspective. Besides, all students had to do two research papers each three weeks. He assessed those papers based on the number of quotes and references. The research livened up the atmosphere a lot and initiated heated discussions touching upon the nineteenth and the twentieth century photography, review of students’ own works and the critical approach in general. Photography criticism made important part of the course.

Did those critical discussions aim at helping students to gain the necessary vocabulary? Coke said they didn’t use any special terms. It was more about pulling out parallels from the past: for instance, what Sadakichi Hartmann had meant? what Coffin had said on that? And so on.

What did Hilton Kramer once say? And what was John Zharkovsky’s opinion of Walker Evans? Did the same refer to certain other people? What was the difference between expert criticism and a critical review of somebody who learned photography through practice. Those were the things they talked about day by day. Van Deren Coke didn’t think there were any systems in that field to elaborate and believed all approaches had equal worth. He said they talked so much that they finally gained some insight and each student learned to comment on any work – something of his fellow-student or a total stranger.

Franck Van Deren Coke had a huge collection of images at home and often used it for reference. He had gathered the collection with the very purpose of conducting lectures. For instance, the discussion was about Ansel Adams. Coke would pull out a file containing a dozen of his photos and ask the students to show the qualities they ascribed to Adams. He would select a picture himself and ask the same question again. He was not impressed by the pathetics and taught the students that if they asserted something they should be ready to put a finger on it. He said to them that he wanted to see it with his own eyes. When you adopt this kind of approach, people become more careful of what they say – particularly those with the gift of the gab or just garrulous. Assert something? Prove.

Students were free to determine how their dialogue with Professor happened. They were free to come up and discuss whatever was on their mind, show their own photos for the past couple of weeks or just throw a heap of pics occupying their thoughts currently on the teacher’s table. It was a group of people knowing one another very well. And they also knew how everything had developed from the beginning. Looking at Ansel Adams’, or Strand’s, or anyone else’s work they learned to express their attitude in some osmotic process and they learned to give criticism using historical analogies. Drawing parallels from history was probably the only common factor in the studies, according to Van Deren Coke.

Each week, each month, each semester was different. He said they didn’t follow a particular program but everyone who enrolled for the seminar knew he would have to do a lot of written papers. At first, most of them wrinkled their noses, but gradually students learned to express their thoughts on the paper – with variable success. Essays and papers were read out aloud for the rest of the audience.

Usually they wrote about the same subject and then the reading out took place. Thus, they wrote for other students, not for the teacher.

Developing the ability to speak your thoughts out aloud probably also helps students to acquire the necessary vocabulary and terminology?

According to Van Deren Coke, what they sure did was talk photography till they got blue in the face. They really spoke a lot. But his seminar was not the only one. The same student attended other lectures, as well, and likely took two more art history courses – say, painting after 1950 and art in the USA in the interwar period – all this running parallel. If people were afraid that Franck Van Deren Coke’s influence would be one-sided, they had to consider the balancing power of other teachers. Coke’s own opinions differed from those of other lecturers, and thus the students were presented with at least two points of view.

The result was the product of students’ meeting a whole array of teachers with their own opinions. Once in semester, all students had to make a report on their progress. The report was to last about three hours and be delivered in front of the audience. After their presentations students received questions from teachers, one of whom would be a photographer, others – an artist, a ceramist, an art historian and someone from the artistic department. They would all take a look at the student’s photos, but not all of them were experts in photography. Some might even rather associate the word ‘grainy’ with caviar. The issuing discussion could look something like this: I paint pictures on canvas, you render them in light and dark on film – let’s talk about images in general. The discussions could be quite heated and were very frank because they had to decide whether the student should be advised to continue education or not, determine what assistance he could get, and so on.

When asked how his teaching career helped – or hindered – his own photography, Franck Van Deren Coke said that once a month he brought about a dozen new images of his own to the seminar and discussed them with his students the same way they discussed other students’ works. Professor left the question open whether he had succeeded or failed. His own photos were mostly autobiographic and reflected his interest in history. Students knew that just as well as he knew each of them and their mind. It was an opportunity for them to grill Van Deren Coke in return like his: you said to us this and this but are you really trying to say that with this image? I cannot see it, where is it? You always taught us to find the right form of expression…

But did Professor himself find it? Van Deren Coke said he wanted to show students that when it came to practice, teachers faced with the same problems. They just had more experience and their own alphabet contained more letters, so to say, than were necessary to compose words but the difficulties and the doubts were the same.

Did he consider this way of teaching a necessary part?

He said, he did not know, but that was how he taught. At the beginning of his teaching career he was wary of showing his works to students – feared they would copy-cat him. But in a few years of teaching he realized one thing: those who were independent in their thinking could endlessly watch others’ work – whoever’s signature may be there – without detriment to their own discernment. The fact that they were watching the teacher’s photography did not change anything. While the presence of the professor promoted genuine dialogue and feed-back.

Franck Van Derek Coke did not show the students his works for quite long – at least until he started doing exhibitions.

But then he realized that was wrong on both sides.

When prompted, that this approach helped him get feedback not only from his students but from his own critical self, he said yes, exactly.

Franck Van Deren Coke said he always gauged his students’ reactions. He communicated with carefully selected photographers. For instance, one year they chose four from 100 applicants. Even if the college were slack in their selection process, they would still get primary material. His students knew how to observe and what to say. Professor treated them as his junior colleagues. And he was more interested in what they had to say about his work than all those people who hanged his photography in their drawing rooms because its style suited their mood.